The seeds of our primary interface with machine intelligence rest in the humble origins of the vending machine. Here is the brief story of this evolution of self-service.

The Process and Technology of Self-Service

Not that long-ago, shop clerks pulled merchandise for us from high shelves behind a counter. Today, we push squeaky, wheeled, metal baskets around the well-lit warehouses we call supermarkets. Tomorrow, we’ll click a link and a drone will plop a quart of fresh raspberries at our door.

Innovation in retail shopping—as with all service businesses—happens through shifts in business processes and technologies. Automated self-service fuses process and technology so customers can serve themselves.

In the agriculture and manufacturing sectors, automation boosted output for traditional producers like farmers and factory workers. But in the service economy, automation improves the productivity of end users. This raises interesting questions about the future of work, but those will have to wait for a future article.

In this article, I examine the evolution of automated self-service—both its underlying business processes as well as its technologies.

Self-Service Processes

Self-service is, first and foremost, a business process. Business processes are activities that are linked together to generate value for a business. In some cases, the activities are internal—like managing inventory systems at Amazon or assembling a Ford F-150 truck. In others, they are externally focused, such as assisting Safeway shoppers at checkout or helping couples plan their retirement at Schwab.

Self-service is a particular way of organizing business processes for these customer-facing activities. Through it, end users can interact with a business with minimal, and in many cases no, contact with employees. Self-service can reduce labor costs and it can increase operating scale.

Cutting Costs

Self-service kiosks let Alaska Airlines employees spend less time fussing with boarding passes and baggage tags. This saves labor costs and there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. With the right guidelines, automation is part of how society becomes more efficient with its resources over time. The question is how the resulting costs and benefits are shared among stakeholders.

Automated self-service is uniquely abusive when it shifts work from paid employees to unpaid end users. That is simple cost externalization; something that’s particularly galling when it doesn’t add value—like many self-checkout machines at supermarkets. Author Craig Lambert refers to this phenomenon as “Shadow Work.”

Boosting Scale

Self-service can also greatly increase operating scale. When Piggly Wiggly opened the first self-service grocery store in 1916, customers no longer needed clerks to reach shelves. Pushing a shopping cart is work, but it’s a choice we willingly make for the added speed, convenience, and freedom. This business process breakthrough helped Piggly Wiggly greatly increase the scale of shopping by eliminating clerks as a bottleneck. It was an innovation that ended up paving the way for modern shopping.

Operating scale provided access to the large quantities of data needed to fuel the next wave of self-service: machine learning.

Self-Service Technologies

While self-service business processes don’t always rely on technological innovation, most of the time they do. Automated self-service has gone through four fairly distinct phases in underlying technology: mechanical, electrical, digital, and now machine learning.

Mechanical and Electrical Devices

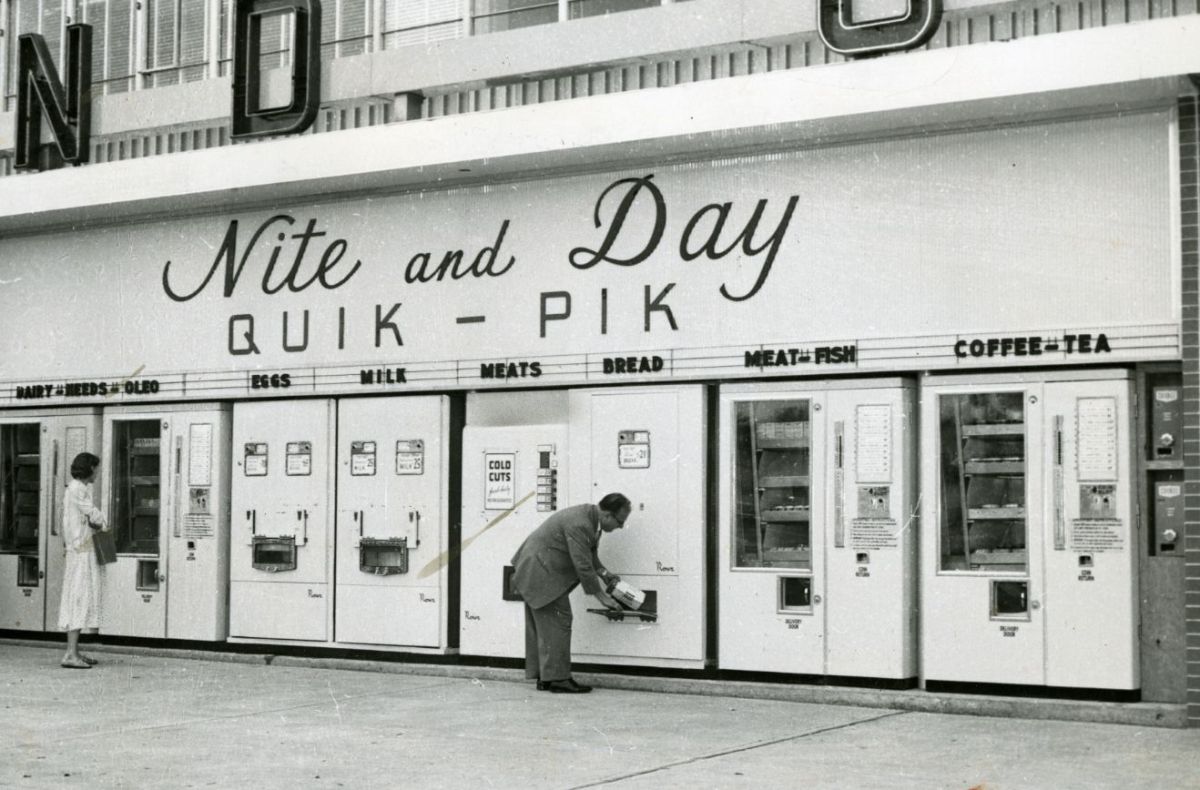

Self-service technologies trace back to at least 215 BCE, when Hero of Alexandria developed a coin-operated, holy water dispenser. Its basic mechanical principles were still used over two thousand years later to dispense stamps, candy, cigarettes and all kinds of things. Later, as electronics emerged in the 20th Century, vending machines inherited a whole slew of new capabilities. By the 1940s, we had machines for dispensing everything from coffee and ice cream to Campbell soup and even worms.

Digital and Machine-Learning Devices

The Automated Teller Machine, or ATM, was the first real example of digital self-service machines. Its processing power and data networks didn’t just prove critical to real-time coordination with a complex banking system. They also proved useful for a new generation of digital self-service machines like gas pumps, ticket machines, and self-checkout machines.

These same capabilities also made their way into our homes through personal computers connected to the Internet. The result was a new and extremely versatile medium for two-way communications. Amazon, Google, and Netflix enabled us to shop, search vast archives, and watch movies all on our own. These innovations, in turn, gave rise to a new generation of self-service technology based on machine learning.

We are now at the outset of this fourth generation of self-service platforms, whose distinguishing characteristic is its uncanny intelligence. Uber uses machine learning technology to identify suspicious accounts and optimize pickup and dropoff points. Amazon, Google, and Facebook use it to personalize our experience and optimize their revenues. And Creator uses it to crank out one gourmet burger every thirty seconds in its stores.

The Emerging Interface

Self-Service Scale Builds Intelligence

Automated self-service has been driving down the cost of labor for a long time. In fact, you could say that cost-cutting drive is a foundational element in most business automation. It functions as a kind of “code within the code” in enterprises that optimize for shareholder primacy.

What’s new is the way fourth-generation self-service technology uses scale to fuel an upward spiral in intelligence. The move to web interfaces allowed companies to serve people in numbers never before imaginable. With that scale came an ocean of user data that has proven essential to training machine learning algorithms. These algorithms are the source of modern competitive advantage. They are also extending self-service into a growing number of service markets once assumed to be too complex to automate.

Our Point of Contact with Machine Intelligence

Machine learning is thus accelerating the automation of the service economy. Services account for 80 percent of jobs and GDP in the United States. As this huge segment of economic activity automates, it will look very different from earlier automation in agriculture and manufacturing. That’s because services rely on coordination with end users. To automate services, businesses need to automate their engagement with end users.

As more and more of the service economy automates, automated self-service interfaces become increasingly important. When you learn to recognize these interfaces for what they really are, you see that they are everywhere. They already guide our online searches, shopping, banking and ride sharing—and they are really just getting started. More and more of our days will be spent interacting with these increasingly powerful interfaces. Automated self-service is thus becoming humanity’s primary point of contact with machine intelligence.

It is for this reason that it is important to understand the evolution of these systems. Our emerging new partnership with machines will be mediated by the automated self-service interface.

Increasingly, I find myself preferring the self-service, no personal contact method of doing things. I remember when catalog ordering involved calling an 800 number, talking to a person (usually after a wait), saying the item number often more than once, size, color, etc., spelling my name and address, etc. Now, ordering online works so much more quickly and efficiently. Many sites such as Chewy and Amazon store most of my information, such that I can place an order with just a few keystrokes, I shortly receive shipping and tracking information, and the item is in my hands often the next day. My human nature side is concerned about all those nice people who I used to deal with on the phone, and what are they doing now for a job, but my selfish side is glad I don’t have to waste time and deal with them! Moral dilemma?

Indeed, Bill. I know exactly what you mean, even if it’s not easy to admit it. It’s clear that your buying this or that or my buying this or that individually doesn’t have an impact on any one person’s job. But collectively, along with everyone else, it does. It’s a kind of tragedy of the commons in that sense, I guess.

Ordering online is a bit more like the days before 1-800 numbers, when you had to fill out a physical form to send in along with a check.

Hadn’t thought of it this way before, but when you exit a Wal-Mart after using one of the self-checkout kiosks, it’s like you’ve just been inside a gigantic vending machine. Viewed in that context, and from the vendors’ perspective, ever-increasing automation simply makes sense.

And the involvement of large amounts of human labour was only ever temporary.

We need to decouple income from employment, providing a floor at first, below which no one can drop, before evolving to a technologically-enabled triumph of the commons — where not only will no one ever have to trade their time and effort for money in order to survive, but our grandchildren will be able to live comfortably without ever having to “get a job”. If you feel enterprising, and/or have a marketable talent, maybe you can be more than comfortable — but if you fail, you won’t fall below that floor.

I’ve said it what feels like a thousand times before and I’ll say it again:

“If the robots are going to take all the jobs, they’re going to have to start paying for everything.”

It’s not as if automation will stop advancing. The curve of technological acceleration is exponential, and is already getting pretty steep.

As to “shadow work”, well, we’re all going to have to fill in the gaps here and there, adjusting to the fact that machines don’t always operate in ways similar to what humans do. Without employment, we’ll have a lot more time on our hands anyway and, with our basic income being at first very basic indeed, we’ll be doing a lot more things ourselves, just to save money.

In the process, people will realize how much there really is to do outside of “work”, may very well find MORE meaning in those activities than they did at their jobs.

Then if that’s not enough, there will still be plenty of things to do. The beauty of it is, your participation won’t necessarily be contingent on compensation.

Automation is our friend — so long as we don’t balk at the word “socialism”. Government works for us, not the other way around. Now that we’ve reached the point where technological displacement threatens to crash the economy and send us into a dystopian nightmare, it’s already a little late to start redistributing tax revenue to citizens.

“If the robots are going to take all the jobs, they’re going to have to start paying for everything.” That is a great line. This is a point that I will be building to in future posts. In a consumer-driven economy, like ours, when consumer spending loses a critical mass of the income-generating engine of employment, the economy will inevitably begin to sputter and oscillate until a new pattern stabilizes.

I am a believer in Basic Income, but I don’t think it solves all of our problems. I also worry that it could function as a centralization of power, when what we really need is just the opposite. That said, I think that it will be important to injecting some form of economic stability in the disruption that is headed our way.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, Fil. Sorry you had troubles posting it originally.

On my 5-mile bike ride home along Pennsylvania and Wisconsin avenues in DC, I pass a Whole Foods, a Trader Joe’s, a Safeway, another Trader Joe’s, a boarded-up Whole Foods, a Giant, and the construction site for a Wegmans. No self check but plenty of staff at the Trader Joe’s, lots of self-service checkout at the Giant, no self-service checkout at the Whole Foods. Giant, through PeaPod, offers online ordering and home delivery of groceries, as does Whole Foods. That approach seems to add staff, since you need someone in the store (or warehouse) to pick the order — at Whole Foods, it tends to be pickers working in the store. Plus you need the delivery truck driver. The true breakthrough here would be to use that Windows 10 “see through someone else’s eyes” capability to have a robotic picker of produce so you can make sure you get the best tomatoes and properly ripe avocados.

I was very interested in the Creator — I hope they’ll offer Impossible burgers as an option — but I wouldn’t consider that innovation a self-service automation. It’s automating the back end of the restaurant, the cook. They have it on display because it’s novel and cool to watch, but it could just as well be doing its work behind the scenes, and the customer interaction would be no different. Ditto for the Zume pizza referenced in the same link.

The part of the service economy I work in deals with disability compensation claims processing. Here, we’re just beginning to experience the impact of robotic process automation. This is a more generalized application of machine learning techniques to specific repetitive tasks, such as logging in the receipt of new compensation claims, and classifying them based on the type of disability received, plus ensuring that name and contact information is updated properly. It involves working with multiple different computer applications. Apparently robotic process automation can sit on top of the different applications, be granted similar login privileges to the humans who currently operate the applications, and then study the activity patterns that show up in the systems — including being able to “view” the incoming documents — so that they can “learn” the rules that current employees follow when doing the work. I’d be interested to get your take on the spread of robotic process automation, I think its general purpose applicability will cause substantial disruption in a number of different task areas.

Thanks for dropping by and for the thoughtful comments, Phil.

We’re in the early days still of supermarket automation. It’s fair to say that the initial employment impact will be at the front of the stores. If you haven’t yet visited an Amazon Go convenience store, I encourage you to do so. Using machine vision to track what a user puts into their basket is a real breakthrough. It totally changes the experience. On the back end of the store, I agree. We are already seeing experiments with “dark stores,” where grocers set up special sections of their store set aside specifically for pickers so that no regular customers clog up the works. Picking has been a notoriously difficult task for robots to master, but researchers are making progress. Meanwhile, companies like Ocado are building back-end inventory management and picking solutions that will eventually show up in grocery stores all over the place. The new jobs doing this work today, are simply a less capital-intensive way of bridging between today’s system and where things are headed, at which point capital investments will be made to lower total costs.

That’s a good point about Creator. I should probably stop using them as an example of automated self-service. Hook that up to a front-end kiosk and you have an integrated system, but the way they’re building the burgers is not, in itself, automated self-service. Thanks for pointing that out.

Robotic process automation is set for a huge take-off. Not so much in service industries per se, but more in knowledge management, which is to say white collar jobs. There’s overlap, but you can have white collar work in agriculture, manufacturing and services. What’s interesting about RPA is that right now it relies on a lot of clunky kludges to replace what industry observers call swivel chair work (people swiveling back and forth in a chair between two different consoles as a way to integrate systems). That kludginess gives it the kind of flexibility to get the job done, even if often it’s not that graceful. The real giant that will emerge here is my old employer, Microsoft. They just recently announced some important moves in this direction, but when you think big picture, while there are many ERP systems to contend with the output UI is often Microsoft Office. Microsoft is still king of knowledge workers. The RPA market is theirs to lose, in my opinion.

Super glad you stopped by.

Ordering online is a bit more like the days before 1-800 numbers, when you had to fill out a physical form to send in along with a check.

Hadn’t thought of it this way before, but when you exit a Wal-Mart after using one of the self-checkout kiosks, it’s like you’ve just been inside a gigantic vending machine. Viewed in that context, and from the vendors’ perspective, ever-increasing automation simply makes sense.

And the involvement of large amounts of human labour was only ever temporary.

We need to decouple income from employment, providing a floor at first, below which no one can drop, before evolving to a technologically-enabled triumph of the commons — where not only will no one ever have to trade their time and effort for money in order to survive, but our grandchildren will be able to live comfortably without ever having to “get a job”. If you feel enterprising, and/or have a marketable talent, maybe you can be more than comfortable — but if you fail, you won’t fall below that floor.

I’ve said it what feels like a thousand times before and I’ll say it again:

“If the robots are going to take all the jobs, they’re going to have to start paying for everything.”

It’s not as if automation will stop advancing. The curve of technological acceleration is exponential, and is already getting pretty steep.

As to “shadow work”, well, we’re all going to have to fill in the gaps here and there, adjusting to the fact that machines don’t always operate in ways similar to what humans do. Without employment, we’ll have a lot more time on our hands anyway and, with our basic income being at first very basic indeed, we’ll be doing a lot more things ourselves, just to save money.

In the process, people will realize how much there really is to do outside of “work”, may very well find MORE meaning in those activities than they did at their jobs.

Then if that’s not enough, there will still be plenty of things to do. The beauty of it is, your participation won’t necessarily be contingent on compensation.

Automation is our friend — so long as we don’t balk at the word “socialism”. Government works for us, not the other way around. Now that we’ve reached the point where technological displacement threatens to crash the economy and send us into a dystopian nightmare, it’s already a little late to start redistributing tax revenue to citizens.

“If the robots are going to take all the jobs, they’re going to have to start paying for everything.” That is a great line. This is a point that I will be building to in future posts. In a consumer-driven economy, like ours, when consumer spending loses a critical mass of the income-generating engine of employment, the economy will inevitably begin to sputter and oscillate until a new pattern stabilizes.

I am a believer in Basic Income, but I don’t think it solves all of our problems. I also worry that it could function as a centralization of power, when what we really need is just the opposite. That said, I think that it will be important to injecting some form of economic stability in the disruption that is headed our way.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, Fil. Sorry you had troubles posting it originally.

On my 5-mile bike ride home along Pennsylvania and Wisconsin avenues in DC, I pass a Whole Foods, a Trader Joe’s, a Safeway, another Trader Joe’s, a boarded-up Whole Foods, a Giant, and the construction site for a Wegmans. No self check but plenty of staff at the Trader Joe’s, lots of self-service checkout at the Giant, no self-service checkout at the Whole Foods. Giant, through PeaPod, offers online ordering and home delivery of groceries, as does Whole Foods. That approach seems to add staff, since you need someone in the store (or warehouse) to pick the order — at Whole Foods, it tends to be pickers working in the store. Plus you need the delivery truck driver. The true breakthrough here would be to use that Windows 10 “see through someone else’s eyes” capability to have a robotic picker of produce so you can make sure you get the best tomatoes and properly ripe avocados.

I was very interested in the Creator — I hope they’ll offer Impossible burgers as an option — but I wouldn’t consider that innovation a self-service automation. It’s automating the back end of the restaurant, the cook. They have it on display because it’s novel and cool to watch, but it could just as well be doing its work behind the scenes, and the customer interaction would be no different. Ditto for the Zume pizza referenced in the same link.

The part of the service economy I work in deals with disability compensation claims processing. Here, we’re just beginning to experience the impact of robotic process automation. This is a more generalized application of machine learning techniques to specific repetitive tasks, such as logging in the receipt of new compensation claims, and classifying them based on the type of disability received, plus ensuring that name and contact information is updated properly. It involves working with multiple different computer applications. Apparently robotic process automation can sit on top of the different applications, be granted similar login privileges to the humans who currently operate the applications, and then study the activity patterns that show up in the systems — including being able to “view” the incoming documents — so that they can “learn” the rules that current employees follow when doing the work. I’d be interested to get your take on the spread of robotic process automation, I think its general purpose applicability will cause substantial disruption in a number of different task areas.

Thanks for dropping by and for the thoughtful comments, Phil.

We’re in the early days still of supermarket automation. It’s fair to say that the initial employment impact will be at the front of the stores. If you haven’t yet visited an Amazon Go convenience store, I encourage you to do so. Using machine vision to track what a user puts into their basket is a real breakthrough. It totally changes the experience. On the back end of the store, I agree. We are already seeing experiments with “dark stores,” where grocers set up special sections of their store set aside specifically for pickers so that no regular customers clog up the works. Picking has been a notoriously difficult task for robots to master, but researchers are making progress. Meanwhile, companies like Ocado are building back-end inventory management and picking solutions that will eventually show up in grocery stores all over the place. The new jobs doing this work today, are simply a less capital-intensive way of bridging between today’s system and where things are headed, at which point capital investments will be made to lower total costs.

That’s a good point about Creator. I should probably stop using them as an example of automated self-service. Hook that up to a front-end kiosk and you have an integrated system, but the way they’re building the burgers is not, in itself, automated self-service. Thanks for pointing that out.

Robotic process automation is set for a huge take-off. Not so much in service industries per se, but more in knowledge management, which is to say white collar jobs. There’s overlap, but you can have white collar work in agriculture, manufacturing and services. What’s interesting about RPA is that right now it relies on a lot of clunky kludges to replace what industry observers call swivel chair work (people swiveling back and forth in a chair between two different consoles as a way to integrate systems). That kludginess gives it the kind of flexibility to get the job done, even if often it’s not that graceful. The real giant that will emerge here is my old employer, Microsoft. They just recently announced some important moves in this direction, but when you think big picture, while there are many ERP systems to contend with the output UI is often Microsoft Office. Microsoft is still king of knowledge workers. The RPA market is theirs to lose, in my opinion.

Super glad you stopped by.

Increasingly, I find myself preferring the self-service, no personal contact method of doing things. I remember when catalog ordering involved calling an 800 number, talking to a person (usually after a wait), saying the item number often more than once, size, color, etc., spelling my name and address, etc. Now, ordering online works so much more quickly and efficiently. Many sites such as Chewy and Amazon store most of my information, such that I can place an order with just a few keystrokes, I shortly receive shipping and tracking information, and the item is in my hands often the next day. My human nature side is concerned about all those nice people who I used to deal with on the phone, and what are they doing now for a job, but my selfish side is glad I don’t have to waste time and deal with them! Moral dilemma?

Indeed, Bill. I know exactly what you mean, even if it’s not easy to admit it. It’s clear that your buying this or that or my buying this or that individually doesn’t have an impact on any one person’s job. But collectively, along with everyone else, it does. It’s a kind of tragedy of the commons in that sense, I guess.